-40%

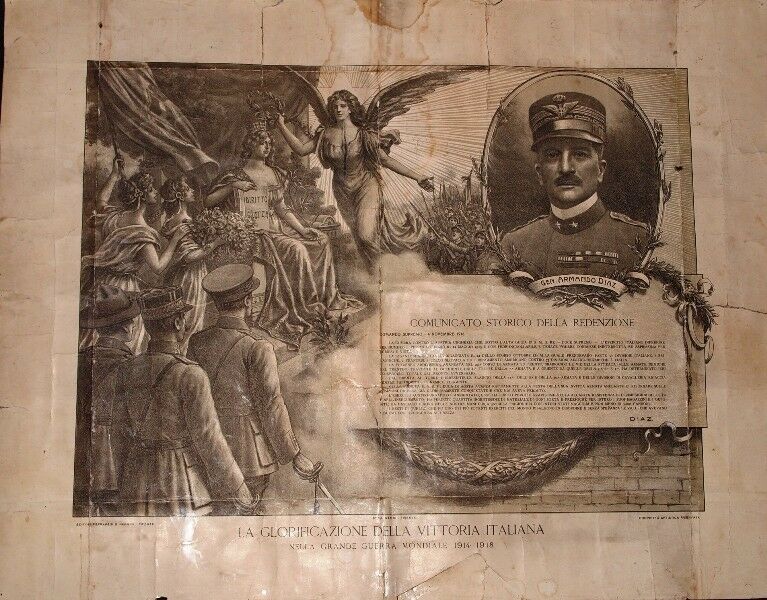

WW1 Italian Victory Medal Original Ribbons SEE STORE WW1 MEDALS COMBINE SHIPPING

$ 29.03

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

PLEASE FOLLOW OUR E BAY STORESEE ALL PICS

SALE

SEE OUR STORE

PLEASE READ WHOLE ADD

Allied Victory Medal (Italy)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

Allied Victory Medal

Medaglia interalleata della vittoria

Obverse and reverse of the medal

Type

Campaign medal

Awarded for

Service in World War I

Presented by

Kingdom of Italy

Eligibility

Italian officers and soldiers

Campaign(s)

World War I

Status

No longer awarded

Established

16 December 1920

Total

Approximately 2,000,000

Ribbon bar of the medal

The

Allied Victory Medal

(

Italian

:

Medaglia interalleata della vittoria

or

Medaglia della vittoria commemorativa della grande guerra per la civiltà

) was the Italian variant of the Victory Medal of other nations. It was established by royal decree number 1918 on 16 December 1920, which granted it to all who had been awarded the "fatiche di guerra" distinction by royal decree number 641 of 21 May 1916, or who had served for four months in an area under the jurisdiction of the armed forces and who had been mobilised and directly worked with the operational army.

A public competition to design it was won by

Gaetano Orsolini

, with his design of 'Victory on a triumphal chariot, with the torch of liberty, drawn by four yoked lions'.

Military history of Italy during World War I

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

Part of

a series

on the

History of

Italy

show

Early

show

Ancient Rome

show

Romano-Barbaric Kingdoms

show

Medieval

show

Early modern

show

Modern

show

By topic

Timeline

Italy portal

v

t

e

This article is about

Italian

military operations in

World War I

.

Although a member of the

Triple Alliance

, Italy did not join the

Central Powers

– Germany and Austria-Hungary – when the war started on

28 July 1914

. In fact, those two countries had taken the offensive while the Triple Alliance was supposed to be a defensive alliance. Moreover the Triple Alliance recognized that both Italy and Austria-Hungary were interested in the Balkans and required both to consult each other before changing the status quo and to provide compensation for whatever advantage in that area: Austria-Hungary did consult Germany but not Italy before issuing the ultimatum to Serbia, and refused any compensation before the end of the war.

Almost a year after the war's commencement, after secret parallel negotiations with both sides (with the Allies in which Italy negotiated for territory if victorious, and with the Central Powers to gain territory if neutral) Italy entered the war on the side of the

Allied Powers

. Italy began to fight with Austria-Hungary along the northern border, including high up in the now-Italian Alps with very cold winters and along the

Isonzo river

. The Italian army repeatedly attacked and, despite winning a majority of the battles, suffered heavy losses and made little progress as the mountainous terrain favoured the defender. Italy was then forced to retreat in 1917 by a German-Austrian counteroffensive at the

Battle of Caporetto

after Russia left the war, allowing the Central Powers to move reinforcements to the Italian Front from the Eastern Front.

The offensive of the Central Powers was stopped by Italy at the

Battle of Monte Grappa

in November 1917 and the

Battle of the Piave River

in May 1918. Italy took part in the

Second Battle of the Marne

and the subsequent

Hundred Days Offensive

in the

Western Front

. On 24 October 1918 the Italians, despite being outnumbered, breached the Austrian line in

Vittorio Veneto

and caused the collapse of the centuries-old

Habsburg Empire

. Italy recovered the territory lost after the fighting at Caporetto in November the previous year and moved into Trento and South Tyrol. Fighting ended on 4 November 1918. Italian armed forces were also involved in the

African theatre

, the

Balkan theatre

, the

Middle Eastern theatre

and then took part in the

Occupation of Constantinople

. At the end of World War I, Italy was recognized with a permanent seat in the

League of Nations

' executive council along with Britain, France and Japan.

Roy Pryce summarized the bitter experience:

The government's hope was that the war would be the culmination of Italy's struggle for national independence. Her new allies promised her the "natural frontiers" which she had so long sought-the Trentino and Trieste-and something more. At the end of hostilities she did indeed extend her territory, but she came away from the peace conference dissatisfied with her reward for three and a half years' bitter warfare, having lost half a million of her noblest youth, with her economy impoverished and internal divisions more bitter than ever. That strife could not be resolved within the framework of the old parliamentary regime. The war that was to have been the climax of the Risorgimento produced the Fascist dictatorship. Something, somewhere, had gone wrong.

[1]

Contents

1

From neutrality to intervention

2

Italian Front

2.1

Italian offensives of 1916–1917

2.2

Austro-Hungarian offensives of 1917–1918

2.3

Italian victory

3

Other theaters

3.1

Balkans

3.2

Western Front

3.3

Middle East

4

Consequences

5

See also

6

References

7

Further reading

8

External links

From neutrality to intervention

[

edit

]

Main article:

Italian entry into World War I

A pro-war demonstration in

Bologna

, 1914

Italy was a member of the

Triple Alliance

with Germany and Austria-Hungary. Despite this, in the years before the war, Italy had enhanced its diplomatic relationships with the

United Kingdom

and

France

. This was because the Italian government had grown convinced that support of Austria (the traditional enemy of Italy during the 19th century

Risorgimento

) would not gain Italy the territories it wanted:

Trieste

,

Istria

,

Zara

and

Dalmatia

, all Austrian possessions. In fact, a secret agreement signed with France in 1902 sharply conflicted with Italy's membership in the Triple Alliance.

A few days after the outbreak of the war, on 3 August 1914, the government, led by the conservative

Antonio Salandra

, declared that Italy would not commit its troops, maintaining that the Triple Alliance had only a defensive stance and Austria-Hungary had been the aggressor. Thereafter Salandra and the minister of Foreign Affairs,

Sidney Sonnino

, began to probe which side would grant the best reward for Italy's entrance in the war or its neutrality. Although the majority of the cabinet (including former Prime Minister

Giovanni Giolitti

) was firmly against intervention, numerous intellectuals, including

Socialists

such as

Ivanoe Bonomi

,

Leonida Bissolati

, and, after 18 October 1914,

Benito Mussolini

, declared in favour of intervention, which was then mostly supported by the Nationalist and the Liberal parties. Pro-interventionist socialists believed that, once that weapons had been distributed to the people, they could have transformed the war into a revolution.

The negotiation with

Central Powers

to keep Italy neutral failed: after victory Italy was to get

Trentino

but not the

South Tyrol

, part of the

Austrian Littoral

but not

Trieste

, maybe Tunisia but only after the end of the war while Italy wanted them immediately. The negotiation with the Allies led to the

London Pact

(26 April 1915), signed by Sonnino without the approval of the

Italian Parliament

. According to the Pact, after victory Italy was to get

Trentino

and the

South Tyrol

up to the

Brenner Pass

, the entire

Austrian Littoral

(with

Trieste

),

Gorizia and Gradisca

(Eastern Friuli) and Istria (but without

Fiume

), parts of western

Carniola

(

Idrija

and

Ilirska Bistrica

) and north-western

Dalmatia

with Zara and most of the islands, but without

Split

. Other agreements concerned the sovereignty of the port of

Valona

, the province of

Antalya

in

Turkey

and part of the German colonies in Africa.

On 3 May 1915 Italy officially revoked the Triple Alliance. In the following days Giolitti and the neutralist majority of the Parliament opposed declaring war, while nationalist crowds demonstrated in public areas for it. (The nationalist poet

Gabriele D'Annunzio

called this period

le radiose giornate di Maggio

—"the sunny days of May"). Giolitti had the support of the majority of Italian parliament so on 13 May Salandra offered his resignation to King

Victor Emmanuel III

, but then Giolitti learned that the London Pact was already signed: fearful of a conflict between the Crown and the Parliament and the consequences on both internal stability and foreign relationships, Giolitti accepted the fait accompli, declined to succeed as prime minister and Salandra's resignation was not accepted. On 23 May, Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary. This was followed by declarations of war on the

Ottoman Empire

(21 August 1915,

[2]

following an ultimatum of 3 August),

Bulgaria

(19 October 1915) and the

German Empire

(28 August 1916).

[3]

Italian Front

[

edit

]

Main article:

Italian Front (World War I)

Italian Front 1915–1917

Italian alpine troops, 1915

The front on the Austro-Hungarian border was 650 km (400 mi) long, stretching from the

Stelvio

Pass to the

Adriatic Sea

. Italian forces were numerically superior but this advantage was negated by the difficult terrain. Further, the Italians lacked strategic and tactical leadership. The Italian commander-in-chief was

Luigi Cadorna

, a staunch proponent of the frontal assault whose tactics cost the lives of hundreds of thousands of Italian soldiers. His plan was to attack on the

Isonzo front

, with the dream of breaking over the

Karst Plateau

into the

Carniolan

Basin, taking

Ljubljana

and threatening the Austro-Hungarian Empire's capital

Vienna

. It was a Napoleonic plan, which had no realistic chance of success in an age of barbed wire, machine guns, and indirect artillery fire, combined with hilly and mountainous terrain.

[4]

The first shells were fired in the dawn of 24 May 1915 against the enemy positions of

Cervignano del Friuli

, which was captured a few hours later. On the same day the Austro-Hungarian fleet bombarded the railway stations of

Manfredonia

and

Ancona

. The first Italian casualty was Riccardo Di Giusto.

The main effort was to be concentrated in the

Isonzo

and

Vipava

valleys and on the

Karst Plateau

, in the direction of Ljubljana. The Italian troops had some initial successes, but as in the

Western Front

, the campaign soon evolved into

trench warfare

. The main difference was that the trenches had to be dug in the Alpine rocks and glaciers instead of in the mud, and often up to 3,000 m (9,800 ft) of altitude.

In the first months of the war Italy launched the following offensives:

First Battle of the Isonzo

(23 June – 7 July)

Second Battle of the Isonzo

(18 July – 4 August)

Third Battle of the Isonzo

(18 October – 4 November)

Fourth Battle of the Isonzo

(10 November)

In these first four battles, the Italian Army registered 60,000 fatalities and more than 150,000 wounded, equivalent to around one fourth of the mobilized forces. The offensive in the upper

Cadore

, near the

Col di Lana

, though secondary, blocked large Austro-Hungarian contingents, since it menaced their main logistic lines in

Tyrol

.

Italian offensives of 1916–1917

[

edit

]

This stalemate dragged on for the whole of 1916. While the Austro-Hungarians amassed large forces in

Trentino

, the Italian command launched the

Fifth Battle of the Isonzo

, lasting for eight days from 11 March 1916. This attempt was also fruitless.

In June the Austro-Hungarian counter-offensive (dubbed

"

Strafexpedition

"

, "Punishment Expedition") broke through in Trentino and occupied the whole

Altopiano di Asiago

. The Italian Army managed however to contain the offensive and the enemy retreated in order to strengthen its position in the

Carso

. On 4 August began the

Sixth Battle of the Isonzo

which, five days later, led to the Italian conquest of

Gorizia

, at the cost of 20,000 dead and 50,000 wounded. The year ended with three new offensives:

Seventh Battle of the Isonzo

(14–16 September)

Eighth Battle of the Isonzo

(1 November)

Ninth Battle of the Isonzo

(4 November)

The price was a further 37,000 dead and 88,000 wounded for the Italians, again for no remarkable conquest. In late 1916, the Italian army advanced for some kilometers in Trentino, while, for the whole winter of 1916–1917, the situation in the Isonzo front remained stationary. In May and June was the

Tenth Battle of the Isonzo

. The

Battle of Mount Ortigara

(10–25 June) was Cadorna's attempt to conquer back some territories in Trentino which had remained under Austro-Hungarian control. On 18 August 1917 began the most important Italian offensive, the

Eleventh Battle of the Isonzo

. This time the Italian advance was initially successful as the Bainsizza Plateau southeast of Tolmino was captured, but the Italian army outran its artillery and supply lines, thus preventing the further advance that could have finally succeeded in breaking the Austro-Hungarian army. The Austro-Hungarian line ultimately held and the attack was abandoned on 12 September 1917.

Austro-Hungarian offensives of 1917–1918

[

edit

]

Main articles:

Battle of Caporetto

,

First Battle of Monte Grappa

, and

Battle of the Piave River

Map showing the Italian losses after the Caporetto breakthrough.

Though the last Italian offensive had proven inconclusive, the Austro-Hungarians were in strong need of reinforcements. These became available when Russia crumbled and troops from the Eastern front, the Trentino front and Flanders were secretly concentrated on the Isonzo front.

On 24 October 1917, the Central Powers troops broke through the Italian lines in the upper Isonzo at

Caporetto

(the modern

Kobarid

) and routed the 2nd Italian Army. The Italian army commanders had been informed of a probable enemy attack, but had underestimated it and did not realize the danger posed by the infiltration tactics developed by Germans.

From Caporetto the Austro-Hungarians advanced for 150 km (93 mi) south-west, reaching

Udine

after only four days. The defeat of Caporetto caused the disintegration of the whole Italian front of the Isonzo. The situation was re-established by forming a stop line on the

Tagliamento

and then on the

Piave

rivers, but at the price of 10,000 dead, 30,000 wounded, 265,000 prisoners, 300,000 stragglers, 50,000 deserters, over 3,000 artillery pieces, 3,000 machine guns and 1,700 mortars. The Austro-Hungarian and German losses totaled 70,000. Cadorna, who had tried to attribute the causes of the disasters to low morale and cowardice among the troops, was relieved of duty. On 8 November 1917 he was replaced by

Armando Diaz

.

The Central Powers ended the year 1917 with a general offensive on the Piave, the Altopiano di Asiago, and the

Monte Grappa

, which failed and the Italian front reverted to attritional trench warfare. The Italian army was forced to call the 1899 levy, while that of 1900 was left for a hypothetical final effort for the year of 1919.

The Central Powers stopped their attacks in 1917 because German troops were needed on the Western Front while the Austro-Hungarian troops were exhausted and at the end of much longer logistical lines. The offensive was renewed on 15 June 1918 with Austro-Hungarian troops only in the Battle of Piave. The Italians resisted the assault. The failure of the offensive marked the swan song of Austria-Hungary on the Italian front. The Central Powers proved finally unable to sustain further the war effort, while the multi-ethnic entities of the Austro-Hungarian Empire were on the verge of rebellion. The Italians rescheduled earlier their planned 1919 counter-offensive to October 1918, in order to take advantage of the Austro-Hungarian crisis.

Italian victory

[

edit

]

Italian cavalry in

Trento

on 3 November 1918, after the victorious

Battle of Vittorio Veneto

Postcard sent from an Italian soldier to his family, c. 1917.

The Italian attack of 52 Italian divisions, aided by 3 British 2 French and 1 American division, 65,000 total and Czechoslovaks (see

British and French forces in Italy during World War I

), was started on 24 October from

Vittorio Veneto

. The Austro-Hungarians fought tenaciously for four days, but then the Italians managed to cross the Piave and establish a bridgehead, the Austro-Hungarians began to retreat and then disintegrate after the troops heard of revolutions and independence proclamations in the lands of the Dual Monarchy. Austria-Hungary asked for an armistice on 29 October. The armistice was signed on 3 November at

Villa Giusti

, near

Padua

. Italian soldiers entered Trento while

Bersaglieri

landed from the sea in Trieste. The following day the Istrian cities of

Rovigno

and

Parenzo

, the Dalmatian island of

Lissa

, and the Dalmatian cities of

Zara

and

Fiume

were occupied: the latter were not included in the territories originally promised secretly by the Allies to Italy in case of victory, but the Italians decided to intervene in reply to a local National Council, formed after the flight of the Hungarians, and which had announced the union to the Kingdom of Italy. The

Regia Marina

occupied

Pola

and

Sebenico

, which became the capital of the Military Government of Dalmatia. It occupied also all

Tyrol

by the III Corps of the First Army with 20–22,000 soldiers.

[5]

Other theaters

[

edit

]

Balkans

[

edit

]

Italian troops in Thessaloniki, 1916

Italian troops played a major role in the defence of

Albania

against Austria-Hungary. From 1916 the Italian 35th Division fought on the

Salonika front

as part of the

Allied Army of the Orient

. The Italian XVI Corps (a separate entity independent from the Army of the Orient) took part in actions against Austro-Hungarian forces in Albania; in 1917 they established an

Italian protectorate over Albania

.

Western Front

[

edit

]

Arrival of Italian troops at the Western front

Some Italian divisions were also sent to support the Entente on the

Western Front

. In 1918 Italian troops saw intense combat during the

German spring offensive

. Their most prominent engagement on this front was their role in the

Second Battle of the Marne

.

Middle East

[

edit

]

Main article:

Senussi Campaign

Italy played a token role in the

Sinai and Palestine Campaign

, sending a detachment of five hundred soldiers to assist the British there in 1917.

As Italy entered the war on 23 May 1915, the situation of her forces in the African colonies was critical.

Italian Somaliland

, in the east was far from being pacified, and in North Africa's

Cyrenaica

the Italian forces were confined to some separated points on the coast. But in neighboring

Tripolitania

and

Fezzan

, the story has a different beginning. In August 1914, during their previous colonial invasion and occupation versus local military and forces of the

Ottoman Empire

, the Italian forces reached

Ghat

, that is, conquered most of western

Libya

. But in November 1914, this advance turned into a general retreat, and on 7 April and 28 April, they suffered two reverses at Wadi Marsit (near

Mizda

) and

Gasr Bu Hadi

(or al-Qurdabiya near

Sirte

) respectively. By August 1915, the situation in Tripolitania was similar to that of Cyrenaica. The conquest of all of

Libya

was not resumed until January 1922.

Consequences

[

edit

]

The

Redipuglia War Memorial

of

Redipuglia

, with the tomb of

Prince Emanuele Filiberto, Duke of Aosta

in the foreground, nicknamed the

Undefeated Duke

for having reported numerous victories in the

First World War

without ever being defeated on the battlefield.

[6]

.

Italy's representative at the

Paris Peace Conference

, which led to the

Versailles Treaty

, was Premier

Vittorio Emanuele Orlando

. Orlando was considered one of the "

Big Four

" with

Premier Georges Clemenceau

of the

French Republic

,

President Woodrow Wilson

of the

United States

, and

Prime Minister David Lloyd George

of the

United Kingdom

. Italy received a bit of the land promised in The Treaty of London but not northern Dalmatia nor Fiume. The expectation to gain part of German colonies conquered by the Allies was also not realized. After long discussions the Italian diplomats left the Conference in protest but were forced to rejoin after the Allies refused to concede to all Italian demands and just went on. The territorial gains were perceived as small in comparison to the cost of the war for Italy. The debt contracted to pay for the war's expenses was finally paid back only in the 1970s. The uncertain socio-economic situation and the broken promises from Allied powers caused heavy social strife which led to the

Biennio rosso

and later the rise of

Fascism

and its leader

Benito Mussolini

.